It has been one of the great privileges of my life to work with Indigenous people in remote regions of the world through my association with Indifly. Indifly partners with Indigenous communities to create opportunities for generational sustainable economies while ensuring cultural traditions are maintained and biodiversity is protected. I put aside a few dollars every month through my Indifly Corps subscription to help keep the projects on track. I have been part of the work and have witnessed the results first hand. But more than that, I have befriended some of the most intelligent, interesting, and capable people in some of the most unassuming places on the planet. I’ve observed how deeply they care for their communities and lands, but also how genuinely grateful they are for the opportunity Indifly provides.

Rewa, a small village in the heart of Guyana, is where it all began. Guyana, the only country in South America where English is the primary language, is home to 15% of the worlds fresh water. A remote village, only accessible by a flight and a long boat ride or an extremely long boat ride, Rewa is in one of the most biodiverse jungles on earth. Think of it as the backside slopes of the Amazon: all the rivers flow north to the Gulf of Mexico. Before we even talk about the angling prize, doing battle with the mighty arapaima, the people, like so many adventures, are what tattoo the experience on your soul.

Davis, one of the Macushi guides, grew on me as my visit progressed, leaving me with an enhanced perspective from a new friend. Davis has this wry sense of humor that crept up on me as he introduced me to the ways of the jungle.

Each morning, we would load into the boats. I was always fascinated that the Mucushi would wear shoes around camp, but before stepping into a boat, or into the jungle they'd inevitably leave their shoes behind — lined up at the base of the make shift dock. I tended to my feet in the opposite way: wearing flip flops around the safely manicured grounds of camp, and lacing up wading shoes preparing for the jungle waters. When I asked about it, Davis turned it right back on me, “How can you feel where you step with those shoes on? You always need to know where you step in the jungle.”

We paddled through hidden jungle ponds looking for the distinctive rolls and listening for the shutter of an underwater munch, which I thought was distant thunder at first as we tried to pinpoint the ancient fish. My American friends and I chatted away. Davis continued to find fish, hold the boat as the fish moved off, then continued to the next spot and then the next. When I ask what we are doing wrong, he simply said, “You chatter like the loudest monkey.” Well okay then — stealth was an overlooked but obvious key.

Stalking the giant arapaima, a living dinosaur, is an unparalleled fly fishing quest. They are big, strong, and spooky. You have to learn the fish and the technique, much like you learn the cadence of jungle life. They are hard to hook and jump with gill clattering power, like a tarpon. Although I ended up catching my largest fish with the head guide, Rovin, a longtime Rewa veteran who has been featured in the River Monsters TV show, Davis was my emotional guide during my visit.

As my relationship with Davis grew, I learned more about his story. Like most of the village men, he had worked outside of the village at a foreign-owned mine. He was gone for years at a time, leaving his family and community behind. The conditions at these bauxite or gold mines are atrocious. He said his arms had sores from the caustic waters used in the mining, and he constantly felt sick and was always tired. Worse yet, he was barely paid enough to afford to send any money back to his family in the village. He was away from his family, taking leave in a cramped apartment with other miners in Georgetown, the sprawling, crime ridden capital city. Guiding for arapaima has allowed him to live at home, raise his children and invest in his community. He said he was happier than he has ever been.

One day, we decided to spend the day at the village school. I had brought a stuffed bear, a griz from my hometown of Missoula, and a notebook. I had gotten the idea from my daughter’s class. They had a bear named Huckleberry whom they would send with parents going on trips who would take a few photos of the bear and describe its voyage in the book. I thought that the children of Rewa could utilize their visitors in the same way. Learn about the world through the eyes of the bear. I spent some time describing what my children’s school and surroundings were like. It is always amazing to me how alike children’s experiences can be, even though we think they are so different. We discussed how the threat of bears was similar to the threat of jaguars. We talked about how my kids played soccer as they did. The simple cinderblock school house could have been anywhere in the world. Letters and numbers circled the room. Posters of food groups, maps of the world, and pictures of animals would be just at home in the mountain west as it was in this jungle classroom. I glanced over at Davis as I described how I had made a living as a river guide fishing, just like the guides in Rewa, only for trout not for arapaima. I thought I could see a slight glint of emotion in the eyes of the stoic Davis. Turns out, his daughter was in the classroom.

When I prepared to leave the jungle, Davis left me with a final thought: “It’s too bad we could not find a Macushi wife for you to stay in our village.” I’m still not sure if he was wishing we could continue our new-found friendship or simply getting in one last jab, insinuating that I was a hard bargain for a suitor.

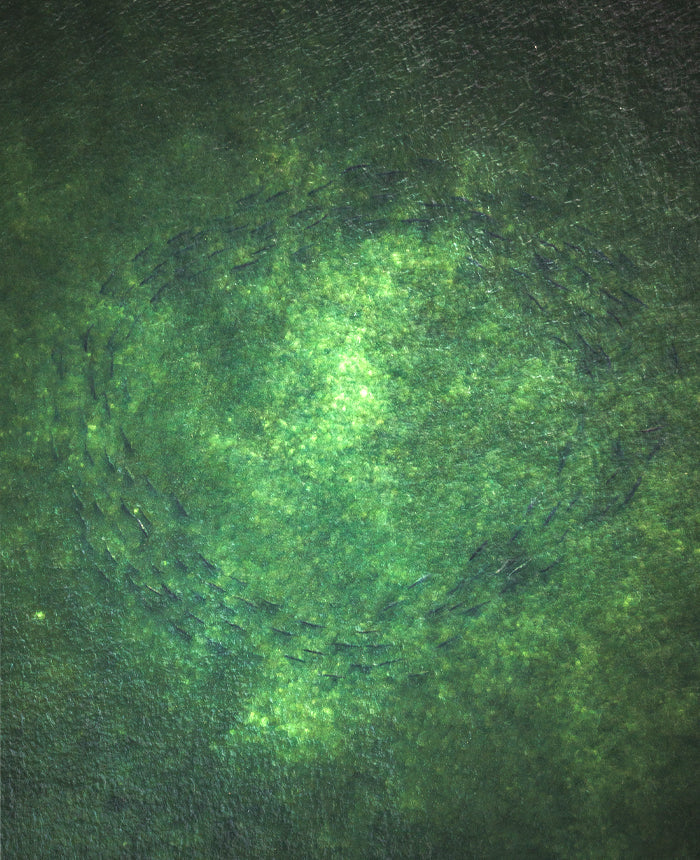

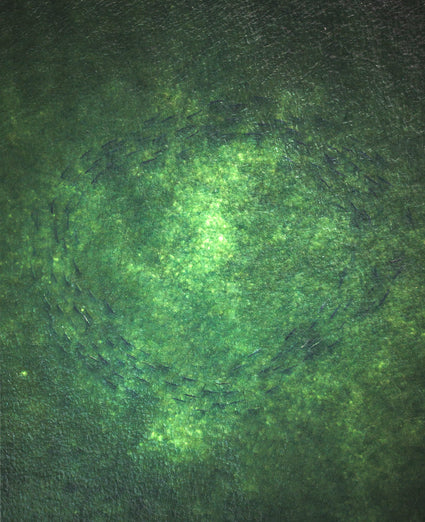

I have had similar friendships emerge in other IndIfly locations. On Anaa atoll, deep in French Polynesia, a project intended to help give younger islanders a way to stay on the island and work, has grown into a resurgence in cultural connectivity. The islands that lie in a ring of the atoll are used for copra production (dried coconut). Those not interested in copra had to look off island for work. Those that stayed used fish traps to harvest and sell bonefish, way too many bonefish, plunging the fishery into decline. This atoll is believed by many Polynesians to be the focal point of the world, with one of the blue holes believed to be a portal between the living and spirit world. It was the central island of a vast naval empire stretching all the way to Hawaii and at one time had tens of thousands of people living on it— royalty, educators and cannibalistic warriors.

Now, the population is shrinking every year with less than 500 people on the island. Children over the age of 11 are forced to go to another island to continue their education in a remnant of the colonial French system. But the Indifly project, which was led by the school children, has not only engaged the entire village in the well-being of the fishery, it continues to rejuvenate Anaa’s cultural heritage. The children took it upon themselves, with the guidance of Indifly scientists to convince the adults and island leadership, to enact an ancient management practice, a rāhui. This ancient practice voted on by the entire community closes fishing during bonefish spawn when the fish congregate and are easy to overfish. The protection of the fish is just one step in enhancing the villager’s way of life. The hope is that the population will grow enough so that they can create a secondary school and keep families together. They have re-engaged in music, art and have developed a more robust infrastructure for tourism creating more good jobs in the community.

I befriended the local musician, Nolan, who teaches the children how to play and sing traditional songs. They serenaded us on a number of occasions, and we joined in sing-alongs to Beatles songs. Nolan, built and tuned the instruments. He taught and passed on traditional and modern songs at the schools. He was a large man, but his fingers played the small 8 stringed instrument with a delicate touch. Nolan later sent me home with a beautiful hand carved instrument similar to a ukulele that I had been coveting. It has strings of fishing line, creating a distinctive plinky sound. I asked for him to sign his name, I flipped over the instrument I was holding on my lap. Nolan had done as I asked. There inscribed, very legibly was inscribed “My Name.” I had a good laugh.

Indifly‘s work on the Wind River Reservation has equally as lofty of goals. The reservation, years ago set aside 180,000 acres in the backcountry, in essence making the first Wilderness Area almost thirty years before the US Congress had given legal meaning to the designation. Under threat from declining economic conditions and the need of young tribal members to find fulfilling occupations at home, Indifly is working with the community to create young guides and infrastructure to not only create economic stability, but as a means to rekindle their cultural relationship to nature.

That Indifly has provided a self-determined pathway for Indigenous people to engage in their community, create viable long-lasting economies and protect their lands and heritage is truly something to witness. Rewa has protected 184 square miles of pristine rain forest. Protecting the arapaima, jaguars, and countless birds, reptiles and mammals in the process. The people of Anaa Atoll have created a sustainable catch-and-release fishery that employs dozens of community members and gives the entire Island pride in their noble heritage. With leaders emerging in the Winds, the future is bright in a community that has seen more than its fair share of trauma. Indifly’s long term commitment to helping these communities is a valuable investment in people, places and fish. Consider joining the Indifly Corps and become a part of the movement.

Peter Vandergrift has been an adventurer, a fishing guide and outfitter, and is a Simms alumni. During his time at sunglass company Costa, Peter worked on Indifly projects both domestic and abroad. He is currently an Indifly board member and chief marketing officer at North Point Brands, whose portfolio includes Cheeky Fishing, RepYourWater, RepYourWild and Wingo Outdoors.